Sinéad Gleeson in conversation with Lisa Jean O'Reilly from Unity Auckland

30 May 2024

30 May 2024

What does a day in the life of Sinéad Gleeson look like?

A day in the life of Sinéad Gleeson probably involves a lot of procrastination. But I have tried to stick to a lifelong habit of getting my writing done early in the morning, before the world crowds in and demands are made of me. There is something special about having it done early because you can think about it throughout the day, ruminate on it, and by the time you go back to it the next morning you’ve had a few hours of it behind you, and you feel it settle, and it creates space for new ideas to come through. When you’re writing something- whether it’s a whole novel or an essay - you’re always thinking about it on some level. It’s always percolating, even when you’re not writing.

You could probably count on one hand the amount of writers in Ireland that are lucky enough to be able to write full time, so the rest of my day is filled with preparing for events like this, or that I will chair with other writers, and at the moment I’m working on an essay about Sinéad O’Connor for an anthology about her life. There is always something!

What does your writing set-up look like, as well as any practices, rituals, or habits you have to set you up for a writing day?

I’m not one of those writers who say that they need a special desk and their totums around them to help them to write. I can write anywhere, and I did used to have a Virginia Woolfe-ian room of my own, but it’s now my son’s bedroom. So I write at the kitchen table, and I write within the chaos and structures of the house. If I’m there, I can’t leave all my notebooks there when I’m finished, so I have to clear them away at the end of the day. But we do have a wide glass door there that lets in lots of light and I love that space. Coming here to New Zealand is such a long way to go, but planes are one of the best places to write because nobody can email you or ask you for anything.

So, I think the idea of rituals and having a special place… It’s useful for some, but I don’t think you need that. I think you need to just show up and write. I have friends who have kids, and they type things into their notes app on their phone, or they leave themselves voice notes to transcribe later. We all make excuses. And there’s a myth around needing three or four hours to write, but no, you don’t, if you have 20 minutes use it. You can get a lot done in 20 minutes that builds up and when you start to see it build up and it becomes a body of work, that’s the most exciting thing.

Did you always want to be a writer?

For a long time as a kid I was convinced I’d be a pilot, but I have dodgy hips so I thought it might not be a good idea to do long haul flights! But I read a lot when I was young and spent a lot of time in hospital, but the idea of being a writer seemed to me to be impossible; something that people would do elsewhere in the world, not where I was.

But then, I remember meeting an author named Tom McCaughran when I was about 10. He lived around the corner from us, and until then I didn’t know that writers were people you could meet. I didn’t know that they were regular people who live in regular houses! The idea of becoming a writer might feel very insurmountable, but all it is, is you’ve got to show up. Do the work and get words down on the page. Of course I wrote bad teenage poetry like a lot of people, but it didn’t seem like a job that you could do or something that was achievable.

The owner of Unity, Jo, is a big believer in bookselling and buying books as being a matchmaking process, like Tinder. Who is your ideal reader or perfect match for Hagstone?

This book is about a lot of things; it’s about art and community and desire and solitude. It’s about democracy, it’s about communities where somebody always wants to be in charge and it’s about autocracy and what power can do. But if I was asked to say one thing about what the book is, it’s about how do you put things in place to live the kind of life that you want to live. Whether that’s that you want to walk the Camino or play on a football team or be a doctor; we all get swerved off the path of where we want to be, and I think the book is about trying to live the most authentic life that you can. The ideal reader is probably somebody who is trying to figure that out; what they really, really want in life.

I believe that the art is as much the artist, as the art is itself. Who are your inspirations?

How do you separate the dancer from the dance? I love that quote from WB Yeats. I think if you’re a creative person, there is a thread that runs through you that means you can’t separate the two. Nell [in Hagstone] is bound to the island that she lives on, and she makes land-art, so literally the sand and the landscape are her. I think a lot of writers write to make sense of the world, so I feel like lots of what I want to say in my writing is about me trying to figure things out, which is me. And as far as my inspirations go; all sorts of people. Growing up, Edna O’Brien was a huge inspiration to me and everyone else because growing up in Ireland the writing canon was very male - we tended to lift up men - and then Edna was out there giving voice to women’s inner lives, which often caused her books to be banned. Anne Enright, is another inspiration to me for all sorts of reasons, she manages to be both literary and funny. Maeve Brennan is one of my all-time favourite writers - I’ve recently written an introduction to her collection of non-fiction The Long Winded Lady; her writing is so elegiac, so real. Her short stories about Dublin are literally set in the house she grew up in - she didn’t even change the address – and that adds an intensity to the work. Visual artists inspire me too, especially Irish artists like Alice Maher, Rachel Fallon, Amanda Coogan, Dorothy Cross. I’ve collaborated with Aideen Barry who makes brilliant video installation work with a lot of humour, but it’s also hugely political. Talking about the female body in Ireland is a very political act. People who make work like that have always resonated with me.

Are you a part of a writing group or do you prefer to work alone?

I’m not part of a writing group. I didn’t write for years because I was working in the arts, around lots of books and authors, and I knew there’d be an expectation around what I might write. I didn’t tell anyone I was writing because I was so terrified and made a pact with myself that if it was terrible, I wouldn’t have to show anyone or send it out. I like working on my own now, but lots of writers I know are a part of a writers group, like one of our best Irish writers Louise Kennedy. I know for some writers, it can be really helpful to keep focussed and to have people critique your work. I like the solitude and work well on my own but there does come a point where you have to give it to somebody else to have a look at it.

As you know, there has been a worldwide surge in Irish voices. Traditionally, James Joyce, WB Yeats, Seamus Heaney and the rest of the lads have taken the limelight, but in recent years the names on bestseller lists have been Sally Rooney, Claire Keegan, Emma Donoghue etc. What do you think has been the cause of this?

For too long, Ireland has been shrouded in huge amounts of secrecy. We’re a country that does shame very well, and have been very good at telling people to dial down their voices, particularly if those are political voices or women’s voices. One of the dedications at the end of Hagstone is to Sinéad O’Connor, who epitomises all of this for me. She was not only a singer but spoke up about representing marginalised communities – trans people, Travellers, AIDS victims – while also being publicly and globally vocal about the horrifying institutional abuse that went on in Ireland. And because of our culture of surpressing voices, I think the rise in Irish writing has actually come from a place where people feel they are in a democratic space and there are stories to be told. Of course, we have a long literary tradition of writers in Ireland - people talk to me about Irish writers, past and present, wherever I go - and that culture is so embedded. Storytelling is primal and ancient and we have always told stories in Ireland, but [women] feel safer now to do that and speak up.

Your voice comes through very strongly in both Hagstone and Constellations; it is courageous, poetic, and entrancing. How did you develop your distinct voice?

To develop a voice - and that’s what writing is… developing a voice that will distinguish you from anybody else that’s writing a book- takes a lot of practice. You write and rewrite, and retrace and reconfigure, and go back over things repeatedly. It’s not necessarily about writing more words, but you get better at whittling it down and making it smaller. I tend to throw everything into writing at the start and then take parts out, peel it back, and start to refine. Voice is a very tricky thing to do though, especially with characters – they need to sound like a real person. You really need to go over your work a lot to develop a strong voice.

When the whale washes up on the beach and Nell sends a photo of its corpse to Cleary instead of naked photos of herself, this was a powerful moment that I couldn’t quite make sense of - it was ambiguous and made the reader work for a conclusion. How much thought did you put into scenes like this?

I have seen washed-up whales and it’s always such a conflicted moment: getting to see such a beautiful creature up close, and an awareness of issues of climate change and endangerment. The whale in that scene is a bit of a Leviathan - which might be seen as a biblical metaphor - but I was just interested in the idea of our time being short – for us, for whales. It lies there spent and gone and there’s all this prurience around how to get rid of it; to chop it up or explode it? For Nell, sending Cleary the whale photo was a way of saying ‘I’m not going to give you what you want’. All through the book, her art and her process are central to her life. She always does what suits her, so I think that the whale is a way to remind Cleary that she calls the shots. It’s a power move, a control thing, that scene.

Finally, what is next for you, Sinéad?

I’m working on a novel. I haven’t written very much of it, and again I need to get further in to see what it is about. I’ve learned with Hagstone, and even with the essays in Constellations, that when you start something, you feel certain it’s about one specific thing. You write your way in and realise that it’s really about something, so I need to discover that with this new book. It’s set in Dublin and I think it’s going to be about friendship but also about property and money. I’m really looking forward to getting back to it, because it’s been a very busy time and it’s hard to write when you’re on the road. Novels are very different to essays, they’re incredibly immersive, so for me, I need to climb into a bunker and pull down the hatch. I’m hoping to do that very soon. The start of a book is always exciting. There are so many forks in the path. It’s probably the best part of writing, the sense of possibility.

Saraid de Silva in conversation with Lisa-Jean O'Reilly from Unity Auckland

28 Apr 2024I also learned that writing a novel requires a lot of your own strength and patience, but also the grace and patience of the people around you. At times I really had to isolate myself to do this, and I’m grateful the people I love gave me that space.

Noelle McCarthy in conversation with Unity Auckland's bookseller Chloe Blades

14 Jun 2023I wanted to explore the beauty and depth and difficulty of life, in Grand.

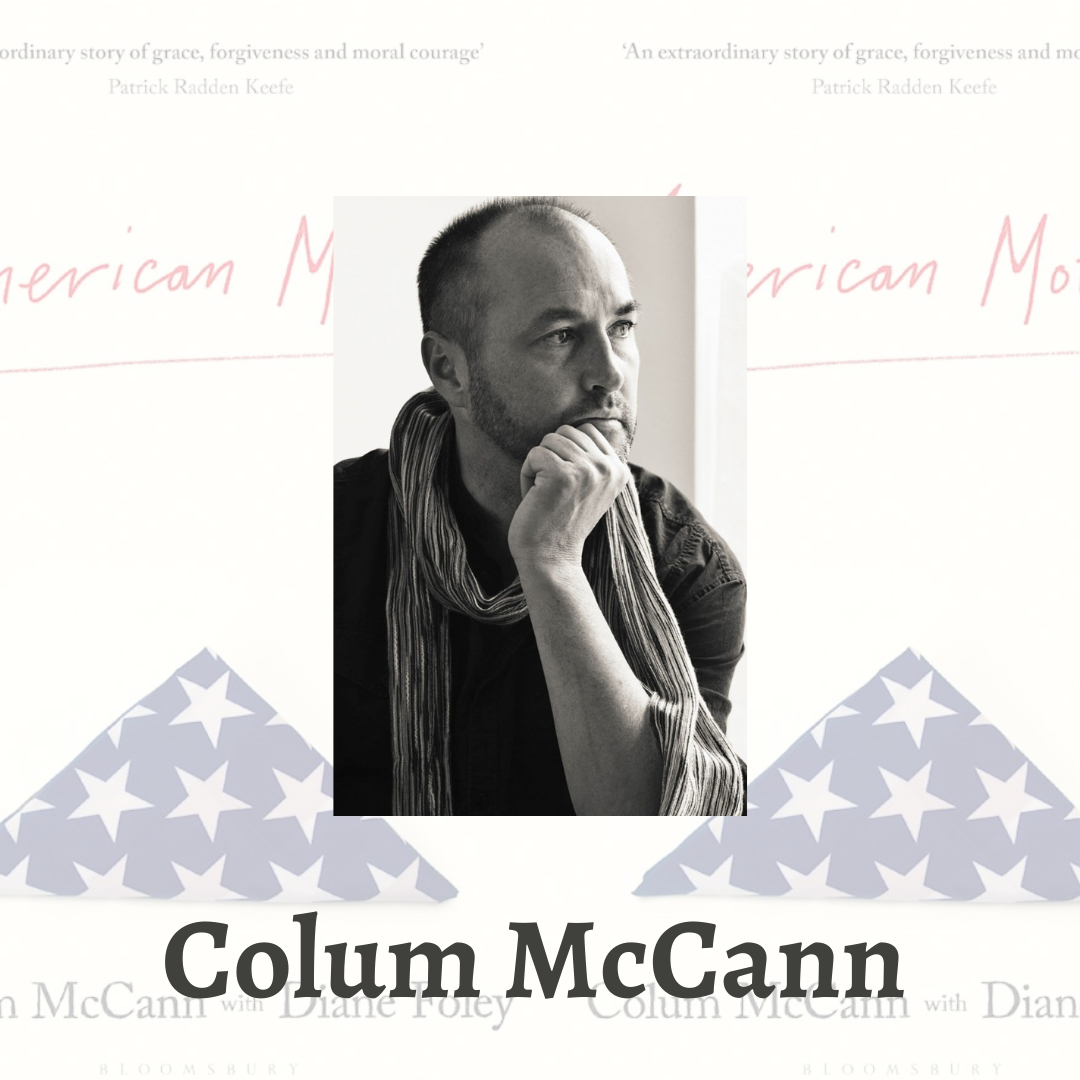

Colum McCann in conversation with Lisa Jean O'Reilly from Unity Auckland

21 May 2024Diane went up to him and said, “Hello Alexanda, I’m Diane, it’s nice to meet you,” and she wasn’t lying. She wanted to be there, and she knew that her son would have wanted her to be there, and her son would have done the same thing. And she also wanted Kotey to know, Alexanda Kotey to know, what he had taken away from the world. And so, it was a powerful moment, and I was a witness to it, and I had to become a ventriloquist to the moment, and that was my job.